Jersey City! Embrace the Grit

Local Stories, Mighty Ivy and the BS in Our Historic Preservation Plan Draft

Focusing on preserving 'high-style houses of worship,' which is just snooty preservation jargon for architectural styles associated and characterized by attention to design details, neglects the cultural fabric woven into structures, often dictated by the financial capacity of the congregation and the time it was built. These buildings—and here I am not only talking about churches but other modest buildings—endure not only due to their architectural grandeur but also because they encapsulate narratives deemed '“worthy” of preserving.

-Nathalie Kalbach-

“Mighty Ivy”: Acrylic Paint, Markers, Pastels, WaxBars - 12x12

Have you ever wondered about the intriguing stories within seemingly unremarkable structures - for example unassuming houses of worship harboring stories, worth of several movies? Forgotten gems, maybe look a little bit rough on the outside, sporadically surfacing as anecdotes, fading into the folds of the unspoken like countless other stories noteworthy to tell.

The church on 20 Ivy Place in Jersey City embodies such a reservoir of untold stories. My exploration began with some hints and a paper for NYU’s Preserving Historic Neighborhoods Class, offering only a glimpse into the narratives connected with this unassuming building.

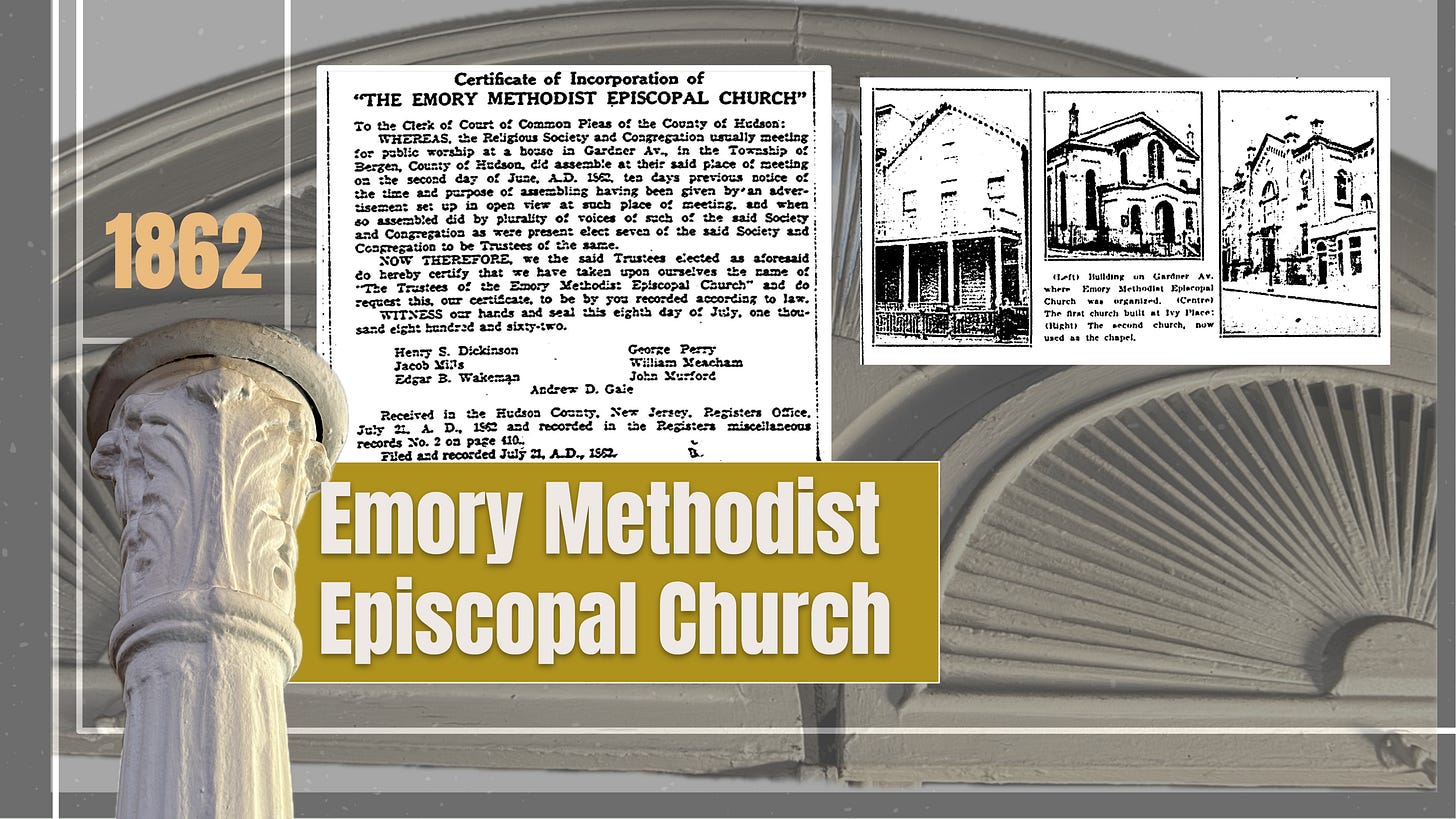

Transport yourself to 1862, when a group met for prayer meetings for young men in the Civil War at Henry R. Welsh’s home on 61 Gardner Street, establishing Emory M.E. Church. The modest brick building on Ivy Place erected in 1863, saw the congregation move away in 1872 to Emory Street, then relocating again and building what is now known as the A.M.E. Zion church on Bergen Ave, where Martin Luther King jr. preached a week before he was killed. But let’s stay with the little church on Ivy Place - sparing you all the research notes.

Enter the First Universalist Church:

Founded in 1871, the First Universalist Church had significant ties to abolitionist and co-founder, David LeCain Holden1 and Phebe A. Hanaford. Hanaford a prominent figure in women’s rights and suffrage.

Hanford assumed the role of the first pastor at the First Universalist Church in 1874 which had moved into the building on Ivy Place. Born on Nantucket Island in May 1829 to a Quaker family, Hanaford became an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate. Before marrying Dr. Joseph Hanaford in 1849, she worked as a teacher. The marriage resulted in two children, Howard and Florence. Hanaford, who through marriage had become a Baptist, eventually converted to Universalism in 1864. Encouraged by suffragist Olympia Brown, Hanaford became the first New England woman ordained to the ministry in 1868. Called to her first church in New Haven, in 1870, she separated from her husband, taking her children and her friend Ellen E. Miles with her.

In Jersey City, Hanaford faced challenges due to her progressive lifestyle and views. As one of only 38 women preachers in the USA, she championed equal rights for women and African Americans, addressing inequality from her pulpit. Hanaford helped ordain her son Howard in 1875 becoming the first woman to do so. Howard was a pastor from 1875 to 1877 at St. Paul’s Universalist Church in Little Fall, NY. During that time Hanaford and her son would “exchange pulpits”, a “queer sight” reported as the “first pastoral exchange on record, between mother and son” in papers outside the margins of New Jersey and New York. Hanaford was also the first woman to officiate the marriage of her own daughter, Florence, in 1876.

Controversies arose due to her close friendship with Ellen Miles, who lived with her and helped with the Sunday school and was lecturing with Hanaford on suffragist and women’s questions. Miles was referred to as the “minister’s wife” and “her man”.

Despite doubling the church membership Hanaford was let go in 1877.

Holden, a founder of the church and President of the Universalist Convention became Hanaford’s best known adversary.

After her dismissal, Hanaford established the Second Universalist Church, attracting about half of the First Universalist Church congregation. Services were held at Library Hall, right across from 20 Ivy Place. Over the years, the Second Universalist Church congregation outgrew the membership of the First.

Hanaford and Miles left Jersey City in 1884, but Hanaford returned several times to give lectures at the Jersey City Women’s Club.

In 1910, living in Manhattan, the census listed Hanaford as the “Head of the House”, while Ellen Miles was recorded as “Partner”. Miles passed away in 1914, concluding their 44-year companionship.

Hanaford published 14 books during her lifetime, the first at the age of 24 titled “Lucretia the Quakeress”, her first anti slavery book. “Life of Abraham Lincoln” published in 1865, was the first biography of the president published after his assassination and sold 20,000 copies. One of her most significant books is Women of the Century, later revised as Daughters of America, a biographical dictionary of 957 notable American Women including scientists, suffragists, war heroes, business women, lawyers, inventors, artists and writers. It was written and published 1876 while she lived in Jersey City. Miles, who was a writer in her own right, helped write the book and it sold 60,000 copies.

Hanaford officiated the funeral service of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. She lived to see the 1920 constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. She passed away on June 2, 1921, residing with her granddaughter in Rochester, New York.

Next act: 1909-1973 Home of the Lafayette Presbyterian Church

Chartered in 1901 by Dr. E. Cannon, the Lafayette Presbyterian Church became the first Black Presbyterian Church in Jersey City. Acquiring The First Universalist Church in 1909, it emerged as a significant institution with a large Black congregation, reaching its peak in 1910 and accommodating up to 600 families.

Dr. E. Cannon, born in Carlisle, South Carolina in 1869, faced the challenges of a racially divided society. Growing up with 11 siblings, he worked several jobs to pay for his education at Lincoln University. Graduating from the New York Homeopathic College with an M.D. degree, he moved to Jersey City in 1893, practicing at his home at 354 Pacific Ave in the Lafayette neighborhood from 1900 onward. Dr. Cannon engaged in the struggle for Black empowerment, organizing the Committee of One Hundred of Hudson County in 1909. This committee, comprised of influential figures like Traverse Spraggins, his brother-in-law and one of the first Black attorney’s in New Jersey, and Reverend Florence Randolph, a missionary preacher dedicated to civil rights, aimed to uplift Black activists.

In 1914, Dr. Cannon co-established and presided over Jersey City’s First Black-owned bank, which helped the African- American community to obtain real-estate loans and other financial services. He also became a franchiser of the Frederick Douglass Film Company (1915-1919), the first cinema company in the nation to produce African-American movies, responding to racist films like “Birth of a Nation”. Dr. Cannon played a pivotal role in politics, seconding the presidential nomination of President Calvin Coolidge in 1924, a historic achievement, as the first Black men accorded this honor.

Dr. Cannon advocated for local protest, notably against a 9pm curfew imposed on all Blacks in 1920. The NAACP held a meeting at the Lafayette Presbyterian Church, and Dr. Cannon led a delegation to protest the curfew at City Hall. His efforts resulted in the curfew’s swift rescindment by the Commissioner of Public Safety. At the time Jersey City was controlled by Frank Hague, who served as a mayor from 1917-1947. Dr. Cannon made a strong case that the mayor’s Public Safety Department should be inclusive and a more accurate representation of the city. On April 1, 1925, just days before Dr. Cannon’s death the very first three Black Policemen were appointed to the Jersey City Police Force.

Dr. Cannon died on April 6, 1925, from injuries sustained in a fall from a public bus on Pacific Avenue. His funeral at the Lafayette Presbyterian Church drew a diverse crowd, including city officials, judges, politicians, and national figures like governors and senators. Among those sending tributes were W.E.B. Du Bois and President Calvan Coolidge.Dr. E. Cannon’s life symbolized the achievements of the Black New Jersey middle class, combining professional, religious and educational pursuits with political activism.

As the oldest continuously used church in the Bergen Hill neighborhood, 20 Ivy Place serves as a gateway into the community, a as a historic marker symbolizing a spiritual center of activism. Despite alterations over time, the building retains its original form and configuration. The memorial stained glass windows, added maybe in the 60s (that I couldn’t find out yet) and funded by African American Families and congregation, contribute to the historic fabric of the church, honoring not only Dr. E Cannon but other influential figures in the local African American community.

Today, the church houses the Orient Church of God. Reverend Rufus V. Strother, whose grandfather, Vincent Strother, was one of the first three Black policemen in Jersey City, being appointed through Dr. Cannon’s efforts in 1925, is deeply committed to his church congregation, and the history involved with the church.

After reading some of the history of the church and looking at the church alongside the remarkable Reverend Strother, my perspective has forever changed. I urge others to discover the rich narratives within this humble church and contribute to its preservation. But not only this church …there are others…and not just churches!

And why share this story now?

Because gatekeeping information and history that is important to our city is BS2 …everyone should be aware, especially considering our city’s recent publication of the Historic Preservation Masterplan Draft.3 As I read through its 250 pages, I couldn’t help but feel profound disappointment at the lack of vision for preserving culturally significant buildings, despite 40% of survey respondents emphasizing it importance.4 Neglecting the essence that makes a building special within the unique history of a city, especially in a local historic preservation plan, is disheartening. Focusing on preserving “high-style houses of worship” which is just snooty preservation jargon for architectural styles that are associated and characterized by attention to design details, neglects the cultural fabric woven into structures, often dictated by the financial capacity of the congregation and the time it was built. These buildings - and here I am not only talking about churches but also other buildings - endure not only due to their architectural grandeur but also because they encapsulate narratives deemed “worthy of preserving.” And let’s ask this question…who determines the worthiness or has determined the worthiness in the last couple of hundred years?

I would love to challenge the nearsighted approach of the Historic Preservation Masterplan Draft and champion a more comprehensive preservation strategy - one that celebrates what everyone loves to point out about this city over and over again: the diversity and culturally rich stories embedded in our local structures, modest or not, gritty or not, vinyl-sided or not, ensuring a vibrant tapestry of history for future generations. Because after all, what else is worth preserving.

Holden is Jersey City’s most known abolitionist, his house at 79 Clifton Place is one of the last known remaining safe houses associated with the Underground Railroad in Jersey City.

Beaucoup de Séraphins - An abbreviation originating from the French celestial slang, literally translating to 'A plethora of angels.' So, when you encounter 'BS,' rest assured, it's not bull; it's just a heavenly surplus! Not to be confused with the more mundane interpretation, ascribing an alternative and less celestial meaning. ;)

Public Comment Period ends March 1st

The survey was part of the public outreach for the HPMP Draft and the results can be seen in the appendix