"By choosing to live here, you're saying you want to be here, you want to be part of the fabric. So I know now that because I chose this, I have the responsibility to learn." Jin Jung

The first time I stumbled across a WERE HERE marker, I was instantly captivated. A deep blue ceramic plaque, fragile and intrinsically beautiful, announced the former location of the Frederick Douglass Film Company. Founded by prominent Black citizens like Dr. George E. Cannon and Reverend W. S. Smith in Jersey City's Lafayette area, this pioneering film production company was established in 1916 to bring films made by African Americans to the mainstream.

According to the research shared on the WERE HERE website, the company created several groundbreaking films in the early 20th century. Their most notable work was "The Colored American Winning His Suit" (1916), which directly challenged the racist narratives perpetuated by D.W. Griffith's infamous "The Birth of a Nation." While Griffith's film is widely studied in film history classes, far fewer people know about these important counter-narratives created by Black filmmakers of the era. What's particularly striking about the Frederick Douglass Film Company's story is how structural racism impacted their reach. Despite initial success, historian John Gomez noted in the Jersey Journal that the company faced systematic suppression from major film distributors who threatened theaters to prevent them from showing films by Black creators. All films of the company are said to be lost. This part of our local history reveals how even in the North, the struggle for representation faced powerful opposition.

Nothing remains at the site today but a parking lot and a fence. The company's physical presence was erased, but thanks to Jin Jung and Duquann Sweeney's WERE HERE project, the story was brought to our awareness.

Stumbling Upon Memory

I say "stumbled" because the marker reminded me of a different project in Europe called "Stolpersteine" (stumbling stones), of which many were located around the area where I used to live in Hamburg, Germany. These small brass plates embedded in sidewalks commemorate victims of Nazi persecution at their last freely chosen residence. The artist behind that project, Gunter Demnig, has a saying that a person is only truly forgotten when their name is forgotten.

When I saw Jin and Duquann's markers, the very same thought came to my mind. These ceramic plaques serve as silent reminders of the people and places that shaped our city but have often been overlooked or forgotten.

In my recent conversation with Jin for the podcast, she shared how her identity as an immigrant influenced this project. "I'm interested in the history of a place that I'm living in because I thought it would help me understand who I was," she told me. This resonated deeply with me as a fellow immigrant who arrived in Jersey City from Germany in 2013. We both found that learning about local history helped us understand our surroundings better and, ultimately, feel more at home.

Jin described how, before creating WERE HERE, she often felt like "it was someone else's place that I was borrowing."

The pandemic gave her space to explore her curiosity about Jersey City more deeply and to "learn to feel at home." The WERE HERE project became both an artistic expression and a path to belonging.

The Art of Remembering

What truly sets WERE HERE apart from traditional historic markers is not just the stories they tell - histories that are sometimes hidden or suppressed - but also the remarkable artistic approach.

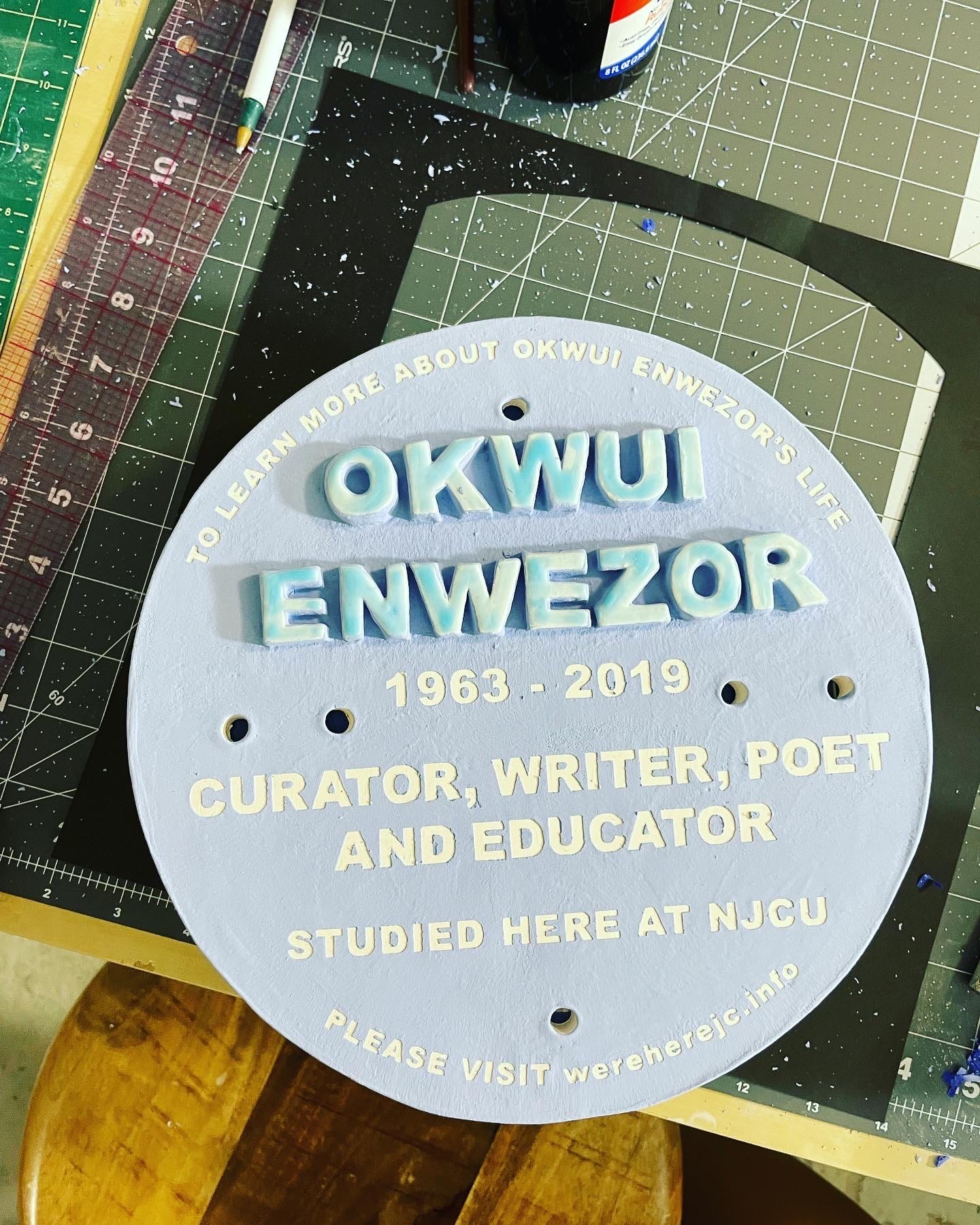

Jin shared with me how she makes each marker by hand: flatten the clay with a slab roller into a slab, cut a circle, form titles in clay, bisque fire, mask the text, brush glaze, and glaze fire it. Once done the captivating deep blue emerges. It's a meticulous process that takes several days.

I didn't ask Jin this directly - and I should have - but I wonder if, while creating these markers with such care and detail, she thinks about the stories and people she's commemorating, pouring her thoughts and emotions into each plaque, all while knowing how fragile they are. When I paint buildings on canvas, I'm mentally transported to that place and time, connecting with its story while also processing my own thoughts and questions. I imagine Jin might experience something similar.

"I thought people would care more when there was someone's hand on it," Jin explained when I asked about her choice of ceramic as a medium. "You could see that someone made it... people wouldn't just ignore it or trash it right away."

She never intended these markers to be permanent solutions. "I always saw those blue plaques as a temporary solution," she said. "I thought that it wasn't my job to place a permanent marker, that I am an artist and not a city official." Instead, she sees them as sparks - gentle reminders saying, "Don't forget to put up a sign here when you have the time."

The name of the project itself carries intentional ambiguity. As Jin explained: "It was supposed to be both 'we're here' and 'were here.' I wanted to connect the present and the past. It is purposely confusing." This wordplay perfectly captures the project's essence - honoring those who were here while asserting that we are here now, responsible for carrying their stories forward.

Stories That Stay With You

Through these markers, I've learned about so many fascinating Jersey City stories I might never have discovered otherwise.

There's the African Burial Ground near Lafayette, where Jin's marker reminds us of the cemetery for enslaved and free Black people that was desecrated and built over. When someone took down this particular marker, Jin - pregnant at the time - was putting it back up when a person from a nearby bodega came out to help, promising to look after it.

At New Jersey City University, Jin recently installed a marker honoring Dr. Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow, who studied at NJCU from 1969 to 1971, finishing her degree four years after his assassination. Jin's poignant reflection on this story, connecting it to her own experience of motherhood and imagining Dr. Shabazz's grief while raising children alone, adds another layer of empathy to this historical recognition.

There's also the story of Navroze Mody, who had moved to the Heights shortly before he was killed in a hate crime targeting people of Indian ancestry. When Jin couldn't get permission from the property owner to place a marker, she and Duquann stood at the site for an hour holding the sign on a long stick, creating a temporary but meaningful intervention. Though Jin described this as feeling "like a failure," she still managed to bring attention to Mody's story and connect with his family, who were grateful that someone cared enough to remember.

Community as Caretakers

"I have to go around town with all the tools in my hands and make sure things are still tied up," Jin told me. "I have to redo the zip ties, redo the wires every now and then. As I do it more and more, I know for sure that that is not my job. It shouldn't be one person's job to maintain something like this. It is unsustainable."

But she's noticed that as people learn about the project, they begin to take ownership. That bodega worker who promised to protect the African Burial Ground marker represents the best of what these artistic interventions can inspire - community care for shared history.

As Jin beautifully expressed in our conversation: "By choosing to live here, you're saying you want to be here, you want to be part of the fabric. So I know now that because I chose this, I have the responsibility to learn."

Looking Deeper

WERE HERE speaks directly to the heart of what I hope to explore through Nat's Sidewalk Stories - how everyday people create meaningful relationships with place through creative interventions. The WERE HERE project reminds us that the streets we walk every day hold countless stories, some celebrated and many forgotten.

If you're in Jersey City, I encourage you to look for these blue ceramic markers as you walk around. Stop, read, and take a moment to connect with the history beneath your feet. Visit WERE HERE to see a map of all marker locations and learn more about the stories they commemorate.

And wherever you are, I invite you to look more closely at the places you pass every day. Consider what histories might be waiting to be uncovered. As Jin has shown, sometimes all it takes is a small ceramic marker to bring these stories back into our collective memory.

Perhaps you might even "adopt" a local historical marker or monument - whether it's one of Jin's ceramic plaques or another memorial in your community. These physical reminders of our shared history need caretakers, people who understand that remembering is an active practice, not a passive one.

Because as both Jin's WERE HERE project and my conversation with her remind us: We are here. They were here. And in the stories we choose to remember and retell, they remain here with us still.

Listen to my full conversation with Jin Jung on the latest episode of Nat's Sidewalk Stories, available on this substack or wherever you get your podcasts.

As an East African, reading about the Frederick Douglass Film Company and the WERE HERE project filled me with pride since these are our distant relatives, and their stories matter deeply. Thank you for sharing

Nat ! This is incredible. Thank you for bringing this endeavor to light for me. I know one of the two creative team members and had no idea this project was happening. So exciting. Thank you ❤️